The summer before starting university is often a time as confusing as it is exciting for soon-to-be undergraduates. If moving into halls, it’s likely to be their first time living away from the family home, or with people unrelated to them ‒ and no matter how many advice guides you read, or the anecdotes told from older friends and family members, it’s pretty much uncharted territory.

However, for those starting at Oxford or Cambridge, there’s even less of a blueprint to follow. With statistics showing that black people make up tiny percentages of new admissions into these prestigious universities (1% for Cambridge in 2015; 1% for Oxford in 2014), many black school leavers will never know what an experience studying there is like. But as relatively small as the numbers are, black students at Oxbridge do exist ‒ and through tools such as social media, we get to see increasing numbers of brilliant, diverse young people take the next steps of their educational lives.

As a new batch of students begin their university journeys, Pride caught up with current students at the University of Oxford and the University of Cambridge to find out about the good, the bad, and the awkward parts of being black people in elite institutions ‒ and how they hope to see themselves reflected in these spaces in the future.

‘How did YOU get in?’

Out of 3,449 students admitted into Cambridge in 2015, only 38 were black; and one of these 38 was Human, Social and Political Sciences student Courtney Daniella Boateng. Currently in her third year of study, Courtney began her YouTube channel after being shocked at how little of herself she saw around her, in an effort to encourage others to apply if they have the academic ability, regardless of background.

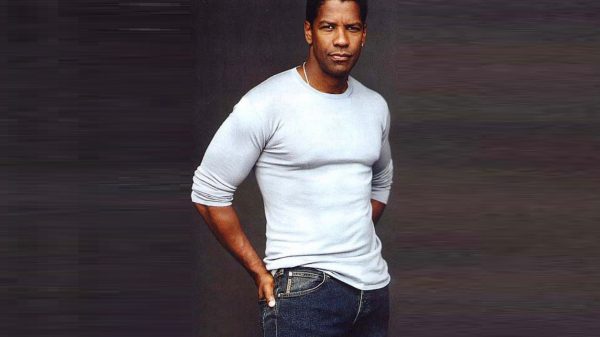

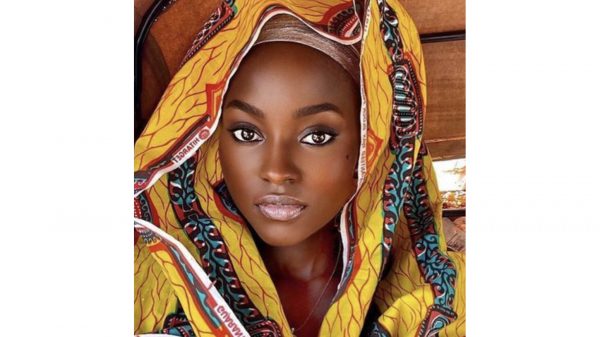

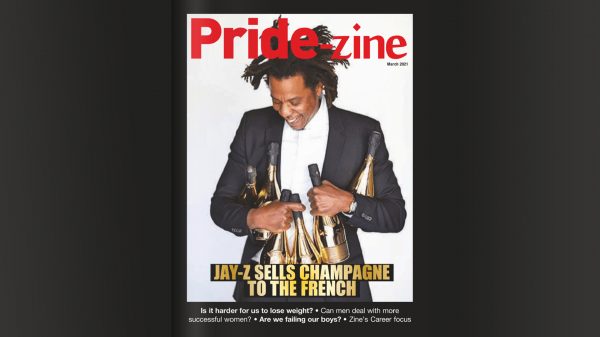

Courtney has been vocal about the belittling comments she has received after encouraging black people to apply to Cambridge and Oxford (Channel 4)

However, in July 2017 she received a lot of new attention after exposing some of the biased and ignorant remarks that she has received from trolls, who have belittled her achievements away as ‘luck’ and have implied that her presence at Cambridge is evidence of admission standards being lowered ‒ rather than accepting that she simply achieved the grades necessary to get in.

‘Do you think I write ‘fam’, ‘rah’, and ‘peng’ in these 2000 word essays that I write every three days and then just get tossed a 2:1?’ she wrote in an illuminating Twitter thread, now shared thousands of times. She further explained some of her experiences with negative comments to Pride.

‘Online, people see a black girl who’s talking casually and using slang with her friends, and they’re confused and assume I got into Cambridge out of kindness or fulfilling a quota,’ she began. ‘That, for me, is why there’s a problem.

‘A lot of people in this country are very protective of institutions they believe are built on British tradition, and of the idea that the epitome of academic excellence in this country must be a white man. In their minds, it can’t be someone who looks or speaks differently, or comes from a less-privileged background, because that doesn’t represent the country, or do it justice. A lot of people have these views and are feeling more and more confident in expressing them during these times of high racial tension.’

Owning your space

Describing the phenomenon of a person feeling undeserving of high achievements, or fearing they’ll eventually be outed as a ‘fraud’, the impostor syndrome is well-known to many who lack some form of privilege (racial, gender, economic) but end up ‘making it’ in spaces of high renown. With expectations of who the ‘traditional’ Oxbridge student is ‒ white and middle to upper-class ‒ it’s unsurprising that anyone who falls outside of these categories may feel similarly insecure when in these spaces.

Taiwo Oyebola, a second year student reading Classics at Oxford’s Wadham College, told of her own initial experience of feeling out of place, and found that it came from internalising outsider expectations of Oxbridge students, rather than active prejudices of her colleagues. ‘At the start, I felt that my voice wasn’t strong enough, or as important as my white counterparts were,’ she admitted.

‘When you’re in a place with high expectations impressed upon you, I think there’s always some form of the impostor syndrome ‒ and when you’re a person of colour, it’s intensified. You panic that you’re there to fill a quota even though your entrance grades speak for themselves; I feel this is a message internalised from the media and perspectives of what the typical Oxbridge student is like. I put these extra pressures on myself by worrying about what other people might be thinking about me, when it wasn’t the case.’

However, she found that support from tutors and friends helped her to shake off feelings of inadequacy, and helped her find her confidence. ‘The tutors have been supportive in reassuring me that I’m heading in the right direction. A positive support network is really important, as they’re helping to encourage you and reaffirm that you’re deserving of your spot ‒ there’s such limited space here, the admissions team wouldn’t waste it on me if they didn’t think I’d end up doing well. Why should I second guess their decision?’

Courtney, of Robinson College, Cambridge, can relate to a similar feeling, and described how wanting to be seen as just as good as her white counterparts kept her in her shell at the start ‒ to the extent where she was afraid of voicing any study difficulties to her tutor. She said: ‘There were people from such elite schools with rich parents; as someone who grew up with one parent on a council estate, at times I was thinking “what am I doing here?” If I couldn’t read my tutor’s handwriting, I didn’t ask them to clear it up because I didn’t want her to think I was dumb.’

But after confiding in an older friend at the university, Courtney came to the realisation that she truly had as much right to be there as anyone else ‒ regardless of whether she was considered a typical Cambridge student or not. She explained: ‘There’s nothing wrong with hard work, but if it’s mainly in an effort to prove myself to others, I’d ruin my own experience. At the end of the day, it’s an amazing university and this opportunity isn’t given to everyone. And from then on, it’s been all about owning my space unapologetically, and really believing that yes ‒ I deserve this.’

Hope Oloye, of Oxford’s Pembroke College, also experienced an element of trepidation about making her voice heard and taking up space in an environment unfamiliar to her. But remembering how hard she’d worked to get into the university was key in her getting rid of that worry ‒ and she was soon elected President of the Junior Common Room.

‘Sometimes I feel as if we, as black people, shy away from getting stuck in in ‘white’ spaces, but there’s so much to gain in terms of networking, new friends and future opportunities,’ she said. ‘Whether you go to Oxford, Cambridge or any other university in this country, black people will probably be in the minority ‒ but we deserve as much of a full experience as anyone else. Don’t feel afraid to get involved in aspects of university life outside of your study, just because you’re “different”.’

Finding your people

Regardless of the university, plenty of black students turn to their university’s ACS (African Caribbean Society) or respective equivalents in order for them to connect with people they have things in common they have things in common with. Taiwo was recently elected as the President of Oxford’s ACS, and describes it an essential network of support.

‘It sounds cliché, but it’s honestly like a family,’ she explained. ‘It’s a network for people who don’t easily find people who look, sound or have the same cultural references elsewhere in the university. It’s somewhere where black students can feel comfortable, and not feel worried about avoiding stereotypes. Studying is hard enough without having to worry about being your full self!’

Hope also found the Oxford ACS helpful in furthering her connections with people with whom she shared common ground: ‘Though I’ve met lovely people in my time here, of course you have the occasional ignorant moments, like people asking where I’m really from, or assuming that I’m best friends with every other black person on campus… for the most part, it comes from quite a good place but when people are from remote villages that aren’t diverse in the slightest, they want to know everything about me because I’m this weird, exotic new thing!

‘Being put under that kind of constant observation was awkward, but when I’d find people from London and from other multicultural areas, it put me more at ease.’

The future

The importance of representation cannot be denied when it comes to the aspirations of younger generations ‒ after all, when you see examples of yourself, it’s easier to imagine yourself achieving the same. And in an effort to encourage potential Oxbridge applicants, much is done by black students to pass down the message that prestigious universities are not limited to white, middle and upper class grammar school leavers.

A particularly positive example came in May 2017, when 14 black male Cambridge students posed for a set of pictures to show that contrary to popular opinion, black boys do go to Cambridge too. The point resonated so much that a group of black male students at Oxford followed suit as part of their own black excellence campaign.

Oxford student Taiwo explained their own efforts to reach out to the next generation of black applicants, including an Annual Access Conference for Year 12 students to get a taste of Oxford life ‒ this year, Stormzy was the guest of honour.

‘It’s all well and good that we’ve made it here, but it’s important that we pull the next generation up with us,’ Taiwo explained simply.

‘If we want Oxford to reflect a different image, the buck can’t just stop with the current few who made it ‒ we have to hand the ladder to others too.’

Of course, there are efforts being made from inside the institutions to diversify the student base as well. Oxford spends over £5m per year on outreach work, while holding over 3,000 outreach events at schools throughout the UK. For Cambridge, there has been a 42% increase in black British students admitted since 2011 ‒ but the work is far from finished. Courtney hopes that she can use her platform to do her part in encouraging people to apply for Oxbridge, especially those who aren’t widely reflected in its halls at the moment.

‘If more people who get their grades apply and don’t get in, then that’s perfect evidence that the university’s admissions process is biased. But until there’s more of us applying, Cambridge can explain the lack of black faces being down to a lack of applications ‒ and I urge to black people considering Cambridge or Oxford not to worry about their background: if you have the grades, just apply!’