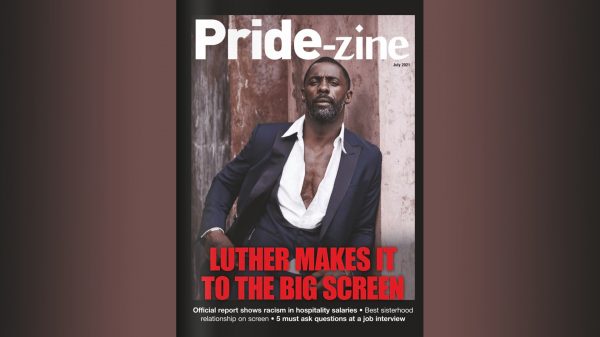

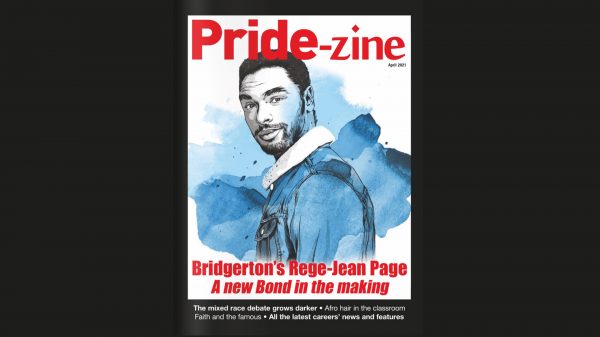

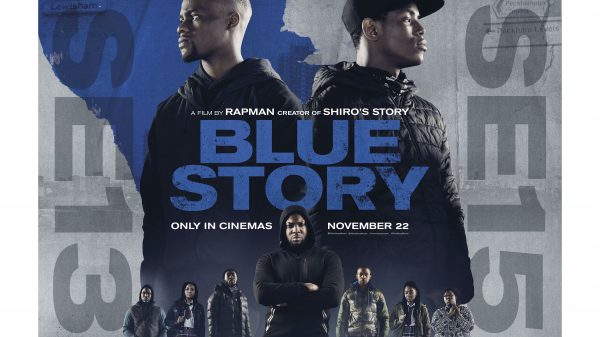

We speak to British-Ghanaian filmmaker Amma Asante about new film Where Hands Touch, the portrayal of romance between a black German girl and a young Nazi, and the difficulties in bringing rarely told histories to the forefront

If you’re familiar with Amma Asante’s work, then you’re already aware of her passion for shining a light on little-known stories from the past. From 2013’s Belle, centring on the biracial daughter of a British admiral in the 18th century to 2016’s Botswana to Britain love story A United Kingdom, Asante isn’t afraid to centre black experiences that aren’t often told.

Her most recent piece is along that vein, and in many ways, stands as the passion project of her life so far. Asante first started looking into developing Where Hands Touch over 10 years ago, after directing her first feature film, A Way Of Life, opened her eyes to the long existence of black communities in South Wales.

‘South Wales is a place that has some of the oldest black communities in Europe, and I kind of didn’t know that until I started working there,’ she explains. ‘And I found it weird that I didn’t know that – why wouldn’t I know the history of other people like me, people of the African diaspora, who aren’t African American, but born in Europe?’

And so began her investigation into black existences throughout the continent, who many of us could stand to know more about. Her research introduced her to the term ‘Rhineland Bastards’, used to categorise the generation of mixed-race children in Germany after World War I (1914-1918), as well as an archived photograph of a young, biracial schoolgirl in a classroom of white people. The question of what must it have been like to experience those times as a German, black, young woman coming of age sparked an idea within Asante – and more than a decade later, she has a film that tries to answer it.

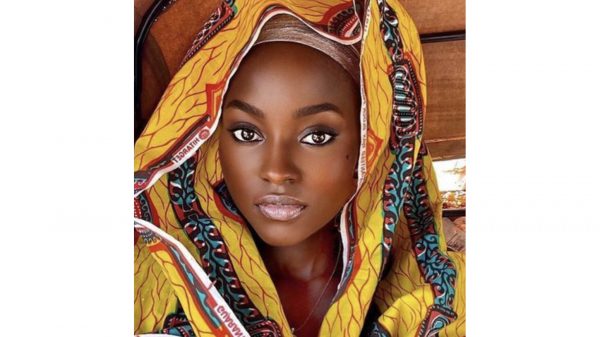

Where Hands Touch stars Amandla Stenberg as lead character Leyna, a biracial teenager in World War II-era Germany. The daughter of a white, blonde-haired German woman and a father she’s never met, who she later discovers was a black soldier who fought for the French, she’s battling her own internal struggles with identity, as well as an outside world who sees her as being ‘different’, while not the immediate target of the horrific Nazi regime. Based on information gathered through years’ worth of Asante’s interviews with Afro-German survivors from the period, and their descendants, the film is likely to be the first time viewers are seeing an Afro-German story set in this time, and is impactful in its uncovering of a significant section of society.

Controversially, Where Hands Touch includes another element of note; Leyna sparks up an ill-advised romantic relationship with Hitler Youth member, and the son of an SS Commander, Lutz (George MacKay). Though both harbour strong feelings towards each other, their positions in society mean that it’s impossible for them to openly engage in the heady excitement of first teenage love – and their story leads far from a comfortable, heart-warming conclusion.

Where Hands Touch is a piece that brims with emotion, with remarkably strong performances from Stenberg, MacKay, and Abbie Cornish, who plays Leyna’s mother, ever fearful for the safety and survival of her daughter. However, it’s fair to say that the film has ruffled feathers throughout its releases and screening periods prior to its UK release this month, with some commentators critical of its depiction between Leyna and, essentially, her oppressor.

We spoke to Amma Asante to find out more about the film’s journey to the big screen, the meanings behind it, and the response to the feedback for the film. (If you’re averse to spoilers, beware: the interview contains discussions of major plot points for the film.)

Where Hands Touch has had a long journey – almost 12 years from you first having this idea, to its UK release this month. How has the story changed from the start?

Amma Asante: I’m quite pure with my ideas in the sense that how I start in the first place is what I end up with; not the specific story, per se, but the world of that story, in which I wanted to see someone who somehow resembles me. The biggest difference really is that when I first started telling this story, I really was purely seeing this world through the eyes of Leyna, the Amandla Stenberg character. Over time, I grew; I became a step-mum, and by the time I made the film I was really strongly identifying with raising a child in a devastating set of circumstances. What could that be like if I were raising, not just any child, but a girl child at a time when she’s coming of age and therefore, not aware of the consequences in the same way as an adult? The political circumstance of what it was to be woman and mother in those years probably changed in terms of my understanding.

In the film, Leyna is the only mixed person in her family – her mother and brother are white. Why was it important for you to create that sense of Leyna being the ‘different’ one in her family?

AA: One reason was because what I understood of these children is that they often were [the only ones in their family], because of the nature of the relationships that the mothers had with the fathers, and how the fathers got to Germany in the first place. They were French soldiers, and at that point, the men weren’t able to stay in Germany – so often times, other children weren’t born. From another standpoint, I was really interested in exploring what survival and persecution look like when you don’t have a community. What happens when your family loves you, but they can’t quite experience life exactly in the way that you are? I think our understanding has often been that as people who are marginalised, we experience it in communities – and actually we don’t really look at those of us that don’t, and that deserves a voice too.

Let’s talk romance. One of the key elements of Where Hands Touch is the relationship between Leyna and Lutz, a white member of the Hitler Youth – they fall for each other. Why was it important to you to include this element, rather than keeping it to the story of an Afro-German girl’s life in Holocaust-era Germany?

AA: When I first looked at the picture of the little girl in the classroom, I wondered how she was negotiating that period. What did that period mean for her, and did she survive? As I started to do my research, what I understood was that where Jewish people were subjected and murdered to the machine of murder, and Hitler’s hatred in the way that we know, for these [biracial] children, there wasn’t a machine. So on an individual basis, something could happen to you, but you also had a chance of survival, which a Jewish person just didn’t have. The predominant group experience that I knew and understood that these mixed children had, outside of murder, was to be sterilised. I wanted to be able to tangibly do a film about what that means; what it means for someone to say: ‘I won’t kill you, but you are not allowed to marry outside of your race, nor are you able to have any relationships outside of your race – when you don’t live in a community that involves your race.’

Quintessentially, what he was saying was that you’ll die out in one generation, by confining these people to a life of solitude. Movies by their very nature are often about people who surmount the odds; when you place them in a devastating situation like the Holocaust, my story was always going to be about someone who surmounted devastating odds, and what was historically correct to her situation. She had to be someone who surmounted the order not to have children.

So, for me, what happens to Leyna in the film isn’t at all to express a love story. The love story is a tool to express the fact that she surmounted the odds in terms of what Hitler had decreed was going to the existence of every child of colour. She doesn’t just surmount the odds in terms of the fact that she falls pregnant; it’s that she keeps her baby throughout that whole process; that she herself survives the process, and her line will continue in the way that Hitler absolutely did not want it to. That makes her a hero. There’s no greater way to be able to express that she avoided his intentions of having her sterilised, and then to place it in a tangible form and show her, pregnant.

The internet is a place for very instant, very vocal reactions – when the film came out in the US earlier this year, it sparked some discussion and controversy over people seeing it as a mainly a ‘Nazi romance’ story. What has your reaction been?

AA: My reaction, first and foremost, has been to respond to the people who have seen it since it came out on Hulu and had greater access to it – which has been overwhelmingly positive. Here’s what I think: first of all, the internet is an echo chamber, so I’m really talking about a really specific area here. But when history has been withheld from you, sometimes you end up doing the work of the people that have deliberately held the history from you. It’s this idea that the voices of only those of us with a story that’s already been told matters, and that a voice that is telling an inconvenient history doesn’t matter, or should be silenced. What you can do is talk about it as much as you like. What it won’t do is stop those of us who want to give those histories voices. My job is not to tell the stories that a minority of people expect me to tell, or order me to tell. I’m not here to always make you feel comfortable. My job is to be the storyteller that tells a story that lives under your skin, that you go and talk about and find out more about that period and what an experience like this might have been like. And if that’s not your interest… It’s not your film. I haven’t made it for you.

‘As women of colour, we need to be open to how each of us is breaking new ground…watch the film and make up your own mind’

How do you get past the frustrations if you feel like your work is being misunderstood?

AA: Right from the get go, you know that you cannot provide content for all of the people, all of the time. You can’t. And if you go into the world thinking that you can, it’s going to be problematic for you. I know that what I do is not for everybody. Whenever you’re doing something that is different and new, and you are different and new in some way, you’re gonna be criticised. But you’re also gonna be providing food – intellectual, artistic food for those who’ve been hungry for it, and those who haven’t had access to it before. So if I’m going to accept that there’ll be people who are hungry for it, then I also have to accept that there will be those who don’t like it as well – and I’m fine with that balance. It’s the yin and the yang.

And finally, for black women who may curious about the film, but also a little hesitant – what would you say to them?

AA: I’d say that as women of colour, we’ve been here a minute – more than a minute – but most of us are still breaking new ground in the areas that we work in; we’re still finding ways to break new ground. If we’re gonna do that, we need to be open to each other. We need to be open to how each of us is breaking new ground. I’m really interested in other women of colour who are breaking new ground, even if what they’re doing has nothing to do with my industry. And I would never, ever, be sceptical based on hearsay; of what another woman, or person was doing, full stop. So I say: watch the film and make up your own mind. You all have brains; you do not need to feed off of the brain of someone else to make up your mind. Just watch it and see. Maybe you’ll hate it; I have a feeling you won’t.

Where Hands Touch is in cinemas now